Part 87

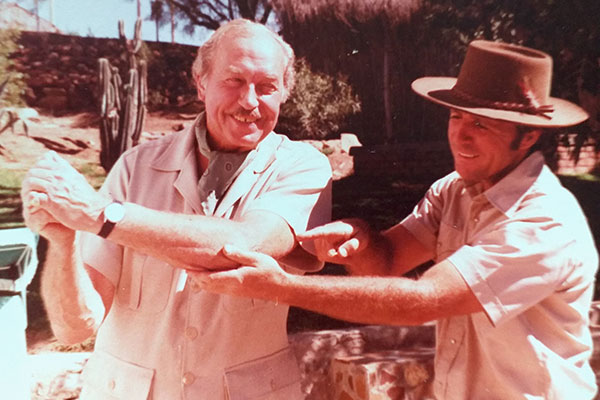

I’ve mentioned my dad quite often in my blogs, but not in great detail. I’ve just spent a few days recently considering what kind of a person he was – in particular, what kind of a father was he to me. I’ll start with his family background which greatly influenced his life, especially as a teenager.

Frank Anthony Andrew Arthur Robert Dresser was born in 1914. With that mouthful of names, no wonder he soon became known as Bob. He was the second-eldest of four children, Enid, Bob, Joy and Guy (known as Buster).

His father was descended from bankers (West Yorkshire Dresser Bank), some of whom came south to London with money. My great grandfather built an even greater fortune in shipping, based in London.

My grandmother Annie Ronald was descended from Scottish aristocracy and had the misfortune to marry into the rather wild world of Dressers. She was a gentle, kindly soul who insisted in her quiet way that the Dresser household should adhere to all the niceties of late Victorian and later Edwardian etiquette. They lived in Hall Place, a large mansion in Weybridge, Surrey, with about 15 bedrooms and a coach house.

The household was run by a couple of maids, a butler, a gardener and my dad’s nanny Clara Allday, who later became my nanny. My dad was sent to school at St. George’s College in Weybridge, reputed to be the second-best Catholic public school in England after Downside in Somerset. He was not academically gifted, but did moderately well at sport (tennis, gymnastics and rugby).

I think I’ll call him Bob at this point. When he was 16, his father (who had inherited a fortune from his own hard-working father), having produced four children with Annie, ran off to Kenya with an actress. His only notable activities up to that point had been as a racing driver on the nearby Brooklands racetrack, competing with famous drivers such as Kaye Don. He was part of the British Winter Olympic team for the bobsleigh and had manned an observation balloon during World War I. One could say that he was a playboy daredevil.

Bob tried to emulate his father in many ways. He and a couple of courageous schoolboys would sometimes dive out of their second-floor dormitory window into the school swimming pool below. On the last occasion that they pulled this stunt, Bob was second in line to dive into the pool. The chap in front of him dived and Bob was poised to follow suit when he heard the terrible sound of a body hitting concrete. The pool had been drained the day before for cleaning. Bob teetered on the windowsill and somehow managed to swing back inside, without following his unfortunate friend (who survived but with terrible injuries).

Shortly after hearing that his father had run off to Kenya, Bob followed suit and ran away from home. He managed to secure a berth aboard an oil tanker bound for the West Indies and ended up in Trinidad. He had paid for his passage but had little money left, and at the age of 16 he looked around for a job.

He was lucky. A few days later he was taken to the northernmost part of the island, put onto a small boat and transported across to the daily incoming ferry from the mainland. His job was to canvas passengers and persuade them to stay at the leading hotel in Port of Spain, Trinidad’s capital. He would also organize their luggage and transport to the hotel, returning the next day to do it all again.

Bob was a handsome and gregarious young man. He quickly made friends and was then offered a job as the manager of a coconut plantation, despite the fact that he was not yet 17. How he managed to cope with the job, I never found out. Presumably, it was mostly supervising the workers and making sure they got paid. During that time, he played rugby for a “West Indies” rugby XV (15 players on a side) against a South American side, crashed a motor bike and survived a hurricane by clinging to a tree.

Returning to the UK at the age of 18, he somehow talked his way into getting a job as a movie sound recordist for Gaumont Films. He worked on the original version of “39 Steps” with Robert Donat as the star and directed by Alfred Hitchcock. About that time, he met my mother Patricia Jean Kathleen Atkins, who had just arrived from South Africa. She was actually engaged to a member of the Bowes-Lyon family who was a cousin of then Queen Elizabeth, wife of King George VI.

Bob worked his charm and they were married two weeks later in a registry office. Both were 21 years old, and Bob really had no idea what to do with his life. I suspect he was just waiting for his father to get eaten by a lion in Africa or something. Not that the old boy left him anything! It also didn’t hurt that my mother had inherited money from her father, who had died at 49. My birth certificate reads: “Father: A.R.F Dresser, Occupation: Retired Film Technician, Age 22.”

Bob was multi-talented. He could play almost any musical instrument by ear. He produced only three or four paintings and a charcoal sketch, but they were really saleable. He wrote some really funny satirical poetry, finally getting a book of poems published at the age of 92. He had an incredibly enquiring mind and had his own theories about almost anything. He was an avid amateur inventor, constantly building gadgets but seldom bothering to patent them or trying to sell them.

On the downside, he was unbelievably dogmatic. He could not be wrong about anything. My poor mother eventually found that the only answer to keeping the peace and quiet was to agree with him, which must have been unbelievably frustrating. He was also very invalidating to me, frequently declaring that I was useless. He would not let me touch any number of expensive toys like model trains and planes he bought “for me.” I could only watch him play with them. He did not have any suggestions for my future after leaving school.

Despite this, he could be terribly funny and would turn on his considerable charm in company, especially if there were any glamorous ladies around.

When I was younger, I was inclined to think that his intriguing ideas about life, the origins of the universe and so on, were very likely true. In later years, I was not so believing and argued with him frequently. It was then that I saw a frighteningly vicious side of him. He would become almost psychotic in his efforts to prove his rightness.

It was very sad as I started to realize that he had no idea how to pursue his real talents. As my mother’s inheritance began to dry up, he did at least try to earn money but in the weirdest ways. When we arrived to live in South Africa, he tried real estate with limited success, then obtained an agency for a powdered toothpaste called Dent-Immune. He visited every dentist in South Africa by car to give them free samples so that they would recommend it. It worked for a while, but it was never going to make his fortune, so he chucked it in.

With the last of the money plus a loan, he bought a fishing trawler in Walvis Bay, Namibia, and signed himself on as crew. After a couple of seasons, he became a “shore skipper.” This meant he sent the boat to sea fully fueled and provisioned while he remained ashore until the boat returned. He would then make sure that the fish factory accurately recorded the catch and paid him accordingly. He made good money for some years, spending his leisure time, when the boat was at sea, going into the Namib Desert and prospecting with mixed success.

As the fishing industry began to fail, he and my mum drove across the Kalahari desert in an Austin station wagon and travelled to Swaziland, a small British protectorate on the borders of South Africa and Mozambique. After a few months advising some Portuguese businessmen on where to place a fish factory in Northern Mozambique, he was thanked but given no reward. He settled into Mbabane in Swaziland, opening a second-hand clothing and furniture store, which did well for some years, before he became an Insurance Investigator, and spent his last working years up to the age of 89 driving to remote villages on his own, following up insurance claims.

I had to admire his tenacity but was frustrated by his tendency to get involved with strange businesses – when he had huge creative talent but never ever followed that through. Tragically, he became an increasingly bitter old man, making my mother’s life hell as well as revealing a lifelong jealousy for my success in film and television.

Had Bob concentrated on one of his real skills like inventing, who knows, he may have come up with something unique and very profitable. Had he been a Peter Warren who has never deviated from his purpose of bringing about a paradigm shift in computing with ExoTech, he might have been a very different person.