Confessions of a Technophobe, New Series 43

Part 4

1976 and beyond

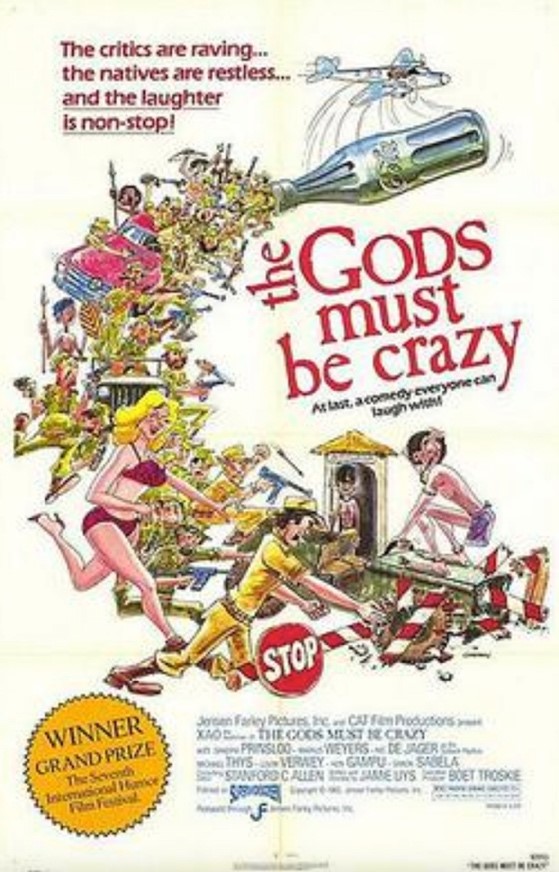

I somehow had enough money to visit Los Angeles to develop my screenwriting skills. I was acutely aware that no one in South Africa at that time (mid-1980s) had acquired the basic skills for writing a screenplay up to the standard of American and British writers. Movies made in South Africa, which attempted to break into the international market, had limited success. There was, however, one exception to this. It was an oddball comedy called “The Gods Must Be Crazy” written and directed by a prolific director of Afrikaans-language movies, Jamie Uys. He was at best a largely self-taught and very average director. However, he was a marvelous storyteller, and his rather strange directorial style somehow perfectly complimented the comedic elements of the “gods” movie.

On a later visit to LA, I met with an experienced director/producer, Eric Karson, who was also involved with distribution. He had an endless fund of stories and anecdotes about the Hollywood movie industry. This included his tale of the day a film was dumped on his desk by the president of the company he was with. The president told Eric, “This is a weird movie. I think it has some potential. Of course, we’ll have to put an American soundtrack on it and do a re-edit but it might just work. See what you think.” Eric watched the picture and went back to the president. He said “You’re right. This movie can work … if you change the soundtrack or even edit a frame of it, you’ll lose its unique and very funny quality.” The president listened and “gods” was released untouched. It ran for two years in France and was well received in the US and elsewhere. In fact, it became for a while the highest grossing non-American movie in the world. Sadly, a sequel was made with a different director which bombed. It was a shadow of the original. Nevertheless, Jamie Uys remains as arguably the most successful South African filmmaker of all time. Coincidently Johann Schutte (who was later to partner with me as both cameraman and producer for over thirty years) shot some of the second unit cinematography on “gods” in the early stages of his movie career. More of Johann later.

I had virtually no contacts on my first visit to LA. The one contact I did have introduced me to a small film company. I showed them my “South Africa, the Best Kept Secret” documentary and this was where everyone present cheered when the American male model Joe, featured in my footage of the Blue Train, appeared. He had worked for them previously. In my quest to learn more about screenwriting I was given the name of Bob McKee, who was recognized as the best teacher of screenwriting in Hollywood at that time. I could not afford to attend one of his seminars, but I was given tapes of his lectures, which completely turned around my screenwriting skills. Bob explained that movie screenplays should consist of three separate acts rather like a stage play except that there were no intervals between each act. Each act performs a specific function designed to hold the interest of the viewer throughout the picture. Briefly, Act One should run about 25 minutes. It should open with what he called “the inciting incident”. This means that the audience should be hooked into the story in the first couple of minutes rather than a long-drawn-out opening. For example, at the start of a film, a man comes out of his house, gets into his car, switches on the ignition and the car blows up. The audience immediately wonders why he was killed and watches carefully as the story unfolds. At the end of Act One, comes the first crisis climax. It’s an “Oh shit” moment when something happens that puts the hero or heroine in jeopardy and the audience wonders how they will get out of it. Act Two unfolds the story in more detail over about 50 minutes and at the end of the act there is another crisis climax, which says “OK, we now understand the problem but how do we solve it? Act Three resolves the problem in the final 25 minutes.

Like any creative structure, it’s only an indicator of what should happen, and it can vary enormously. In recent times the three-act structure has become unfashionable in some quarters, but I personally believe it should still form the basis of a good screenplay, or even a novel for that matter. I then met with a man I shall call by the false name of Ian Jones for reasons that will become apparent later. He was an Englishman who was involved in finding finance for the company. We discovered that we shared the same birthdate although he was a few years older than me. He said that if I had one or more screenplays he would see if he could find the finance for them. I replied that I would get back to him. Another person I met was Dave Walker. His family were in the jewelry business in Chicago, but Dave was obsessed with filmmaking. He confessed that he had never made a movie but he had studied the industry for some years and was confident that he knew more about it than most people in Hollywood. I showed him some of my early screenplays. He was excited about a story I had called “Warhead” but he did not have money with which to commission me to do rewrites that he felt were necessary in order to make it a truly commercial work. As I had written it before my new-found data from Bob McKee, I agreed to do a rewrite when I could but in the meantime I would return to South Africa where Christopher Rowley wanted to make a couple more documentaries and needed my writing and production input.

Encouraged by the two connections I had made, I returned to Jo’burg and in between working for Christopher I rewrote “Warhead” and another screenplay that I originally called “Impi” (Zulu word for Regiment) but is now called “UBUNTU, The Last Warrior.” For Christopher I wrote “One Track Mind,” as well as a film on the town of Walvis Bay, the only port of Namibia. With the growth of the marine container industry worldwide, the small port of Walvis Bay suffered as it did not have the infrastructure or finance to create a container depot. “One Track Mind” came about when Christopher read a newspaper article about a man, Louw Schoeman, a former lawyer obsessed with the Namib Desert. In the article he had explained that one day in the desert he needed to pee. This he did, urinating on the rocks and sand at his feet. To his amazements he saw movement on one of the rocks he had wetted. What had appeared to be an ancient dried brown growth on the rock suddenly burst into life and unfolded to reveal healthy looking green lichen! Christopher contacted Louw in Windhoek, the capital, and discussed the making of a documentary on the desert. In my script I reluctantly skipped the idea of showing Louw peeing in the desert and instead we started the picture by having him use a watering can to pour water on the lichen, with the same result as before.

The Namib is the oldest desert in the world and was formed after an earlier ice age had retreated. It is stunningly beautiful and contains a number of the tallest sand dunes on the planet. It is hard to adequately describe why it is so beautiful. Perhaps it could be better described as majestic. Mile after mile of beautifully scalloped dunes broken up by brutal-looking outcrops of rocks, often eroded into fantastic shapes. Scattered over this wilderness are a handful of oases, with a pool of artesian water that thrust to the surface, with small patches of green grass and occasional thorn bush. It is a haven for birds crossing the desert – including the magnificent pink flamingos. Elephants, rhinos, black mane lions and springbok surprisingly live in the desert. The desert elephants have adapted their feet to splay wider than others of their kind.

We filmed Louw reclining on the grass in one of the oases. He spoke passionately about the desert and how he had forsaken his life as a lawyer in Windhoek to take small groups of tourists into “his” desert. He actually found the greenery in countries like Ireland offensive to his eyes. After we had finished filming his interview, Louw said quietly, “Don’t make any sudden movements, there’s a lion on the far side of the grass. Remain still and he’ll probably go away.” He did just that. Louw later told us that he had seen the lion much earlier but did not want to interrupt the interview!

During the filming of “One Track Mind,” we also found remnants of the camp made by the survivors of the Dunedin Star liner that was wrecked on a shoal off the coast in 1941 during World War Two. All the passengers and some of the crew were rowed ashore only to find that they had landed in one of the most isolated spots imaginable. There was no water and they had little food. Fortunately, the ship had radioed for help before sinking. The South African Air Force flew over the camp and dropped food and water packed inside inflated car tires (no parachutes available because of the war). Many of these packages were destroyed on landing but enough remained to keep the survivors alive. One pilot, Immins Naude, famed for landing planes in impossible spots, flew to the site, landed but got bogged down in soft sand and could not take off again. A convoy was put together manned by raw army recruits from Johannesburg and a line of trucks set out from Windhoek for the 1,200-mile journey to the survivors. In 1941. four-wheel drive had not been invented and the trucks’ tires were ridiculously narrow by today’s standards. As a result, they constantly bogged down in the sand, often traveling as little as 500 yards a day. About ten miles before they reached the survivors’ camp the raw recruits from the city mutinied and refused to go any further. The veteran police captain in charge with the name of “Pump” Smith cajoled a few of them to go ahead with him in just one truck. They arrived at the camp where elderly passengers and babies were almost at the end of their tether and ferried the ship’s passengers and crew back to the convoy. They eventually arrived safely back in Windhoek.

A few weeks later a team arrived overland and succeeded in freeing the plane from the soft sand. Captain Naude and two crew members took off heading for Walvis Bay a few hundred miles south of the campsite. Halfway there, the plane’s engines seized up and Naude had to ditch onto the sea. He and his crew swam to shore but as the plane’s radio was not working nobody knew they had crashed. Naude realized that the team that had brought them to the plane would be heading back to Windhoek. The three men, despite injuries, raced across the desert and just managed to intercept the returning vehicles. Miraculously none of the passengers and crew was lost. I was later commissioned to write a screenplay of the event. We came close to getting a picture funded and even had a ship available to represent the Dunedin Star. I also managed to interview Captains Smith and Naude before they both died in their eighties. They were wonderful, strong-willed and indomitable people who played a major part in the rescue of the ship’s survivors.

Out of the blue I received a call from Dave Walker in Hollywood who told me excitedly that interest had been shown in my “Warhead” screenplay. He asked me to return to Hollywood and work with an experienced screenwriter to polish my story. However, until the screenplay was accepted by the production company, he would not receive any money towards it. Could I find my own way to the US? Sensing that this could be my big break I increased the mortgage on our house, with Hero’s reluctant agreement, and flew over to LA. Dave introduced me to my “experienced” co-writer, who turned out to be a very nice chap, a few years older than me and sadly a complete bullshitter regarding his experience. I quickly realized that for all my shortcomings I knew far more about screenwriting than he did. I persuaded Dave that the guy was useless to the project and thankfully he agreed. So I was on my own. My next shock was the news that the production company wasn’t really interested in the storyline of the screenplay. It was during the American Star Wars period when it was rumored that a few satellites were armed with nuclear warheads in preparation for a war against Russia. My story involved a satellite carrying a warhead that malfunctioned and crashed into the Namib desert. The Americans sent a team to recover it. The Russians sent another team to find it and tell the world what the evil Americans were doing in space. All the production company wanted was the title “Warhead.” They wanted a story around a crazy African dictator who steals a nuclear warhead and holds the West to ransom against the threat of destroying a major city.

Determined to make a success of my trip and fearful that my wife would kill me if I returned empty-handed, I took a deep breath and wrote the new story, bringing in Special Forces from all over the world, including US Navy Seals, UK’s SAS, plus French, German, South African and even Russian specialists. This unlikely team formed an uneasy alliance to recover the bomb and depose the dictator. To my surprise I enjoyed writing the screenplay. It was my first effort since receiving Bob McKee’s writing advice. I went home before finishing the screenplay but sent it to Dave with high expectations. He replied that the production company had dropped the idea entirely and he was no longer connected with them. Net result, my beloved wife didn’t quite kill me, and I now had two unsold screenplays on my hands! A harsh lesson learned about Hollywood. I still firmly believe that perseverance pays off. I currently have seventeen unsold screenplays that are still viable. I sold and have had produced six pictures, two distributed internationally and seven television drama and comedy series produced and screened in South Africa. I’m told that a Hollywood screenwriter is considered successful if 25% of his pictures see the screen, so I haven’t done too badly before becoming a published novelist. Although my writing and the miracle of ExoTech are poles apart, both Peter and I have one thing in common – perseverance. His years of hard work are now paying off, whilst I remain confident that my third novel will have an impact, and I may still see two more films in production before I sail into the blue yonder.