Confessions of a Technophobe, New Series 23

I would describe working as a bouncer as part ruffian and part politician. On second thought, perhaps all politicians are also part ruffian – some more than others! Anyway, I enjoyed the challenge of persuading patrons to either calm down or leave. I considered it a failure if I had to use violence to eject them. I would estimate that about eighty percent of the customers calmed down when warned but some were either too drunk to care or were simply looking for a fight. Even the Greek Cypriots with their knives and knuckle dusters could mostly be talked into calming down. There were exceptions that had to be forcibly ejected. Fortunately, I did not encounter anyone strong enough or fast enough to overpower me.

The closest I came to facing a serious opponent was a very tall and fairly well-built gent who became so arrogant and objectionable that I finally grabbed him, applied the classical Bum’s Rush and threw him out of the door. He tried to come back in, swearing at me, so I reluctantly applied the last remedy open to me. I punched him on the chin. He fell backwards on the pavement. I closed the door and hoped I had seen the last of him. For the next couple of hours all was peaceful but then I looked across at the door and there he was again.

This time I charged across the room before he could enter, but instead of showing aggression he held up his hands in a placating gesture as he spoke to me. “I came back to apologize. I was somewhat drunk. I behaved like an ass and wanted to say I was sorry.” He was clearly genuinely remorseful, so I let him in with a severe warning not to try any funny business. He went to the bar and ordered a beer. He then beckoned to me. I went over to him. He offered me a drink. I thanked him but said I didn’t drink on duty. Nevertheless, we got chatting and he turned out to be a nice enough guy who admitted he only became belligerent after a few drinks. I looked pointedly at his beer and he laughed “Now I’ve sobered up, one beer isn’t going to turn me into the fool I was earlier.”

Having discovered I was South African, he said that as a schoolboy he had gone on a rugby tour over there. It turned out that he had played against my old school Michaelhouse a couple of years before I played for our first team. I remembered watching the game because one of the English schoolboys used a phrase that Michaelhouse had become infamous for. Other schools had teased us unmercifully for many years, using the words “More pressure in the rear, chaps.” We Michaelhouse pupils were already considered to be more English than the English. The stupid expression related to the scrum where eight forwards link to form a solid pack which pushes against the opposing eight players. The ball is then put in between the two packs and they shove each other in an effort to gain control of the ball. The expression “More pressure in the rear” relates to the players packing behind the front row to shove as hard as they can against the backsides of the players in front of them, as they grapple for the ball. The other schools loved to taunt us with this silly expression although it had not been used by us in living memory. I explained to my new friend the reason why the school spectators had screamed with laughter at some point in the game – which we won, by the way.

We parted that evening on a friendly note, and I gave myself half a point for being the politician after the warfare!

Goodness knows what I would have done with my life had I not had another odd encounter in the club. A Canadian came in for a drink. When he discovered that I was South African, his eyes lit up and he said, “I guess you play rugby.” I confirmed that I did. He asked at what level had I played. I told him that after two years in the first team at school I had travelled to South West Africa (now Namibia) to the fishing port of Walvis Bay where my dad was in the fishing industry. I played for the town’s only rugby club. (South West Africa in rugby terms was considered a province of South Africa). It was scheduled to play its first-ever game against an international team in 1955, I was put on standby as a reserve for the South West team. In those amateur days, reserves did not ever get called onto the field to replace another player as they do today. The fact that I was even close to playing against the British Lions was good enough for the Canadian. He told me that if I could find my own way to Vancouver he would get me a good job, provided I played for his rugby club. I was still at the stage in my life when rugby was more important to me than a career. I jumped at the chance and said I would do my best to get there as soon as possible.

Then the reality hit me. I was earning just enough to live on and my chances of buying a ticket to Canada were remote if I continued banging heads together. I asked my fellow bouncer (a former British Light-Heavyweight boxing champion) if he knew of a job that would allow me to save up enough money to pay for a passage to Canada. I was aware that he also ran a film stunt school and asked if I could become a stunt man. He asked me what sports I had played. I replied “Rugby and boxing” leaving out hockey and athletics as irrelevant. He shook his head. “Forget about it,” he said. “I only look for gymnasts and some athletes. Boxers and rugby players aren’t supple enough. You concentrate on strength, not mobility!” He went on to say however that a really well-paid job, if I could get it, was to become a scene shifter for BBC Television. In the 1950s, videotape had not yet been invented and virtually all television shows went out live. A number of scenes were built in one of the huge BBC sound stages. As soon as a scene was completed, the scene shifting crew would move in, dismantle it in complete silence and build a later scene in its place. As the crew worked right next to a live scene being televised, the difficult task of breaking down and building up a scene with props, etc., in silence was a highly skilled task. The crew was very well paid.

I immediately applied for a scene shifting job. Friends laughed at me and said that for every position at the BBC, there would be at least 800 applicants, most of them already skilled in that job. I thought what the hell, let me give it a try. I was granted an interview and frankly I told a pack of lies. I said that I had grown up in South Africa which had no television (until 1976) but for some reason had always wanted to become part of that industry. I added that I had worked my way over to Europe on a cargo ship (true) in order to try and get into TV in Britain (false). I completely oversold myself until the interviewer said, “Hold it. You’ve applied for the wrong job. You should be looking for a position on the production side of TV and I happen to have a vacancy there.” Not really being that interested in the job as such but just wanting to earn good money to get me to Canada to play the game I loved, I asked, “Does it pay more or less than scene shifting?” He was horrified and nearly chucked me out there and then. He finally said, “Look, if you really want to get into TV, surely the money doesn’t matter!” What could I say? And that’s how I got into show biz. The pay was far less than that of the scene shifting posts; I never got to Canada but for the first time in my life I was in a job that I enjoyed enormously and could see the potential for future development.

I was given the curious title of “Call Boy” which I hasten to add is not the male equivalent of “Call Girl”! It relates to an earlier theatre term when very young boys, usually still at school would go and tap on the doors of the lead actors’ dressing rooms and call out “Five minutes, Mr. Barrymore (or whoever)” in order to get them on stage in time for their entry. The TV equivalent had a slightly more elaborate role, but the principle was the same. There were twelve of us in the department. Having just turned 22, I was the youngest by at least ten years. In addition to getting the actors into the studios on time, we also had to make sure they kept their make-up and hairdressing appointments, or sometimes escort them from reception to their dressing rooms, plus a number of unscripted and odd tasks no one else would do.

A few examples at random. The famous American comedian (born in England) Bob Hope arrived early before his dressing room was ready for him. I was assigned to take him to the hospitality lounge and entertain him for half an hour. I was terrified. One of the biggest stars in the world at that time, what could I say to him? In the event he was really charming. He put me at ease, asked about South Africa and we chatted amiably over a cup of tea. The main thing I remember about him, though, was that in the entire time he did not crack a single joke and yet he was regarded as the funniest comic in the world in the 1950s. I later learned that he was no good at adlib gags but had a team of gag writers and an ability to deliver jokes with superb timing. He was also a brilliant businessman and through clever investments he was rated the fifth wealthiest man in the world at one stage.

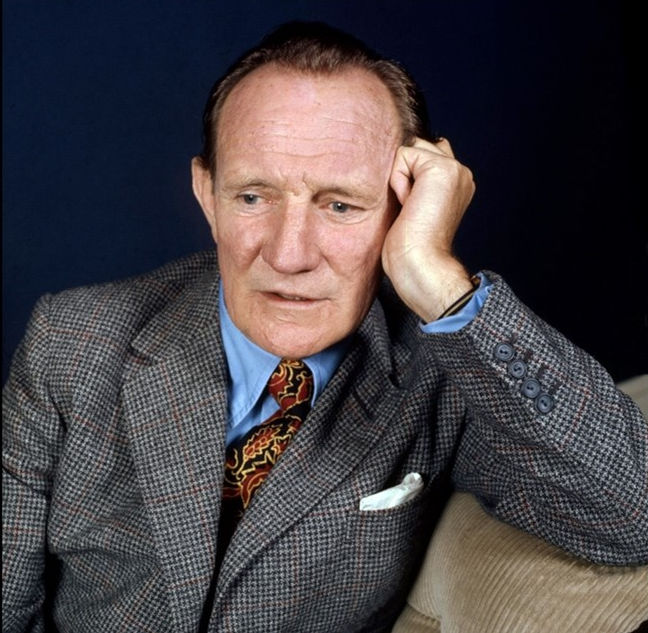

On another occasion I was asked to go to reception and escort the actor Trevor Howard straight to the studio.

I asked if he should not go to his dressing room first. The floor manager (also called studio manager) laughed and said that Trevor was usually drunk, so they always took him straight to the studio, sat him down, interviewed him, then put him in a car and sent him home. I went down to reception and Trevor was reeling around mumbling to anyone who would listen. During my days as a bouncer, I had dealt with a lot of drunks, so I linked my arm in his and cheerfully told him we were going to take a lift (elevator) to the studio. Fortunately, he was a happy drunk, not an aggressive one. We staggered to the lift as it opened. I marched him aboard and we set off to the fourth-floor studio where he was to be interviewed. He tried to chat up a young girl in the lift but she got out at the next floor in horror. Arriving at the studio, I steered him to the chair where he was to be interviewed and left him in the care of the interviewer, an experienced man and former actor. As I retreated, the floor manager shook his head despairingly. “He’s got to do a scene from his latest movie. Dunno how he’ll cope with that!”

Trevor nearly fell off his chair but was helped back and the clock ticked down to transmission time. The interviewer introduced Trevor, then turned to him and asked him about his latest picture. To my amazement, he answered clearly and coherently. A few minutes later he got up and went over to the set prepared for him which consisted of the wall of a log cabin with a window in the middle of it. He disappeared behind the wall and moments later started yelling at another actor also behind the wall. The cameras picked up the two of them through the window as they argued and finally started fighting. The other actor threw a fake punch at Trevor’s jaw. Trevor reeled back, crashed into the window shattering the fake glass and fell out of the window in front of the cameras. He yelled some empty threats to the other actor, then paused, turned to camera and grinned before saying, “The scene goes something like that!”

The interviewer wound up the interview and transmission ended. The crew and producer crowded around congratulating him, but he had retreated into his alcoholic coma again. I had to practically carry him to the lift, prop him up, drag him to the front door where a BBC car was mercifully waiting for him and helped the chauffeur get him seated in the vehicle. He never even said goodbye, but I was suitably impressed by his ability to carry out the interview and re-enact an action scene without stumbling. And I forgave him, in my mind at least.

I worked on a lot of Big Band shows that were popular at the time. The best known perhaps was the Billy Cotton Band, with the gorgeous Silhouettes synchronized dancing troupe. I managed to date one of them, Anne, a couple of times but she had clearly set her sights at dating someone at a higher level than myself who was on the bottom rung of the ladder. The relationship quickly fizzled. The band had an amazing singer, Alan Breeze, who had a wonderful singing voice but was incapable of speech. He stuttered so badly that he either wrote what he wanted to say, or he would sing in a mock operatic voice, “Good morning my boy, how are we today?”

On reflection my years in television now seem like scenes out of Alice in Wonderland. It was all slightly mad but great fun. I’ll give a few more anecdotes next week.

But I won’t be losing sight of the amazing clarity and sanity the evolution of ExoTech is bringing all of us on the team. It’s a bit like unrolling a ball of string as the crazy complexities of current computing are unravelled and laid out in mercifully straight lines!