Confessions of a Technophobe, New Series 19

Part 2 continued

1956–1966

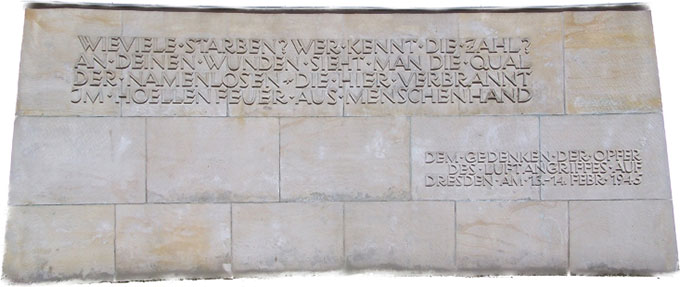

The Loire Valley is a particularly beautiful part of rural France. It was hard to imagine that only ten years previously, the ravages of World War II had just ended. Cities like London, Paris – and even worse, Dresden – still bore the scars of the devastating bombing on both sides. London was targeted by Hitler as a means of breaking the spirit of the British people but all it did was make them more resolute than ever. Paris was occupied by the Germans before they found the need to reduce it to rubble. Tragically, Dresden, a fine, beautiful and historic city in Germany, was utterly destroyed by the increasingly confident and victorious Allies who launched a series of thousand-bomber raids on Hitler’s Vaterland. As a child in Weybridge, I had watched in awe and a degree or terror as the sky was one day filled from horizon to horizon with the sinister shapes of the bombers on their way to Germany. Comprising mainly of Wellington (nicknamed Wimpy) and other medium-sized aircraft, these raids were put together in 1942 to instill fear in the German forces. As with so many attacks by armed forces on enemy targets, many civilians died, as well as the bombers crews reaching the intended military targets. In fact, only three of these raids came close to a thousand bombers and the final raid on Dresden in 1945 comprised 800 aircraft.

The sight of those aircraft and the roar of their combined engines was enough to give me one of my worst moments during WWII even though they were British. Many years later in Johannesburg I became friendly with an artist called Carl Reimer. He had been a child in Dresden when those same planes had dropped their load on the city, reducing most of it to rubble. I think his parents were killed because he spoke of living on the streets for some months before being taken in by a caring family.

As we paddled along the canal, surrounded by peace and quiet as well as lush fields and orchards, I recalled those intimidating days of my childhood in wartime. Only years later did the reality of how children on the then-losing side must have experienced a far greater trauma than mine.

We finally reached the Saône River. Our time of tranquility was rapidly transformed into a scary but exhilarating ride down the wide river that had recently flooded. We were swept downstream at great speed and had to avoid all kinds of floating debris being washed towards the distant sea. We had become rather bored with the unruffled waters of the canals that we had been travelling along. This was more like it. Nevertheless, when we arrived in the city of Lyon and made our way to the nearest youth hostel, we sat down and re-assessed our plan to paddle many more miles on the waterways of Europe. We had travelled 400 kilometers already and felt that by the time we reached our intended destination of Yugoslavia, we would be old and broken men.

My parents had “generously” sent me about £10 to a poste restante (a general delivery address) in Lyon, so we decided to abandon the still waters, hitchhike up to Switzerland and perhaps visit Frau Zamboni, the landlady of the house where my parents and I had stayed, in Bevers, the tiny village outside of St. Moritz.

Our nearest part of Switzerland from Lyon was Geneva. Alan and I decided that we should split up and hitchhike separately. We still had our bulky and unwieldy bags containing both our kayaks and clothing. From previous experience we realized that to hitch the same car would simply not happen.

When I sat down to write these recent blogs, I had no idea that I would spend so much time on my canoe adventures. Thinking about it, I realized that there were two periods in my life when I felt truly free and happy. The first was the year I spent in Walvis Bay and the Namib desert. The second was paddling across France. Not that I was particularly unhappy the rest of my life. I’m not and never have been a depressed person, but those two periods represented the vast potential of my life ahead. I had no specific goal other than a love of rugby and in fact all forms of sport; I had absolutely no idea of what I wanted to do or could do; so I simply enjoyed the world around me and the interesting people I met.

I think Alan was more focused. He wanted to experience life in Europe and Britain, then return to Walvis Bay where he planned to set up a marine salvage company where he could use his skills as a diver to disentangle fishing nets from propellers of trawlers or scrape the undersides of smaller ships and coasters plying their trade around the coasts of southern Africa. He did return to Walvis Bay, set up his company, married a local girl, had a small tribe of children and was well content with his life. When filming in Namibia in later years, I would usually stay with Alan and Monica and was delighted to see that Alan had a prosperous business, a charming wife and great kids. I was never jealous of Alan’s success and was happy for my good friend.

Meanwhile, I struggled to the outskirts of Lyon with my heavy and shapeless bags and saw a truck parked on the roadside. I approached the driver’s cab and looked inside. The driver was fast asleep. I waited for a few minutes in the hope he would wake up, but he didn’t stir. Plucking up my courage I called out “Excusez Monsieur, je veux voyager à Genève.” He woke with a start and looked at me furiously. He replied, speaking fast in a patois of French I could hardly understand, but after having cursed me for waking him up he indicated that I could get in, he would take me some of the way.

We travelled for some hours. I tried to converse with him in my limited French. Once he had recovered from being woken up, he turned out to be a friendly fellow but because of language difficulties it was already late afternoon that I finally realized that he was heading for Grenoble, not Geneva. When I reiterated that I had to link up with my friend Alan in Geneva, he insisted that I would prefer Grenoble!

I had acquired a list and map of French youth hostels from Lyon and found a small hostel marked on the map on the way to Grenoble. It was also about ten miles from the road to Geneva. I finally persuaded my reluctant driver to drop me off at the hostel, so that I could somehow cross over to the Geneva Road the following day. So far, the two hostels we had stayed at in Paris and Lyon, were quite large but this one was clearly much smaller. The driver dropped me at a farmhouse and drove off. He insisted that it was the right address. I knocked on the door and was greeted by a friendly man who spoke a little English. I asked where I could find the hostel? He smiled and replied that I was at the right place. He then led me to a nearby barn, which was empty save for a pile of hay. He indicated that I should sleep on the hay and if I wanted to pee, I was free to go into the bushes on one side of the barn. That was it! No food, no water, no toilet and no bed. For the honor of sleeping there he charged me five francs. Maybe I should have gone to Grenoble!

The hay was reasonably comfortable. At least I had a sleeping bag. The following morning dawned bright and sunny. I had not heard a single vehicle drive past on the narrow country road next to the farm. I waved goodbye to the farmer who was tinkering with his tractor. He told me to wait and disappeared into the house. Moments later he reappeared with a mug of fresh milk and handed it to me. It was creamy and delicious. It undoubtedly saved my life! I gulped it down, waved goodbye to the farmer and staggered off down the road, with a bag over each shoulder.

I’ll never know how I managed to walk the ten miles to the turn off to Geneva. The sun beat down and it grew hotter by the minute. The weight of the bags was not so much the problem. It was the sheer awkwardness of one long bag with the wooden frame of the canoe and the other bag filled with clothing and the canvas “skin” of the kayak. I had also, in a moment of intense stupidity, packed both a tennis racket and a sports jacket for my trip across Europe. Total madness!

About three hours later I arrived dripping with sweat and every bone in my body aching with the effort of lugging the bags ten miles along a deserted road. Then I was quickly rescued by another lorry driver who took me all the way into Geneva and even dropped me outside the much larger youth hostel where a relaxed and refreshed Alan gloated over the single lift that had brought him into Switzerland. He had even been treated to a fine lunch at a routier (a transport café) along the way.

We tried to get some work in Geneva but if France was difficult, Switzerland was impossible. We even met a somewhat mad scientist who worked at the local atomic research laboratory. He told us to call him by his nickname Spatz (Sparrow) as he said his real name was unpronounceable. He was horrified by our story that we could not get work in Switzerland and promised to sort it out. As the money from my parents dwindled away, we called at the café every day. Spatz cheerfully insisted that he was working on it. As a professor, he had some status in the city but after a week he sadly announced that even he could not break through the bureaucracy regarding work permits for foreigners.

We decided that we should have a paddle on the lake in our kayaks. Mindful of Swiss rules and regulations, we contacted the Canoe Club de Genève and asked if it was OK to put our craft into the lake? One of the committee members thanked us for asking permission and told us to go ahead. He then asked to see our kayaks, so we assembled them on the jetty in front of the clubhouse. In moments, another four or five members clustered around excitedly discussing our boats. The committee member turned to us and asked “Would you be interested in selling them to us?”

It turned out that the Swiss government had banned the importation of certain luxury items and kayak was on the list. The man explained that our crafts were of superior quality to anything they could obtain locally. To our amazement he then offered to pay us more than we had bought them for in the UK.

We quickly decided that with the money he offered we could probably hitch to Italy and pick up a secondhand motor scooter, like a Vespa or Lambretta, and continue our tour of Europe in style. We agreed to the deal and left a few days later feeling very rich.

The moral of the story is that if you have a quality product you can get a good price for it. In the case of ExoBrain, the system is for hire only at a very reasonable monthly fee – but of a vastly superior quality never-before-seen in computing. A win-win situation like our sale of kayaks and ExoBrain!