Confessions of a Technophobe, New Series 18

Part 2 continued

1956–1966

We spent a wonderful couple of months in St. Helier, capital of Jersey. We were loaned a tent by the lady in charge of the local Girl Guides and camped on her lawn. She didn’t supply us with any Girl Guides but spoiled us rotten in other ways, such as with samples of her delicious home cooking. We both found jobs in the only genuine coffee bar in town, operating the Gaggia coffee machine. Fortunately, we had both worked in coffee bars in London and nobody else on the island seemed to know how these machines worked! Nevertheless, we were still impatient to get to France and start our voyage across the waterways of Europe. The Times newspaper of St. Helier interviewed us asking about our proposed adventure. We answered, adding that with our very limited budget we needed to find a way across the sea to France. We were contacted by the chairman of the local yacht club who said that the annual yacht race between St. Helier in Jersey and St. Malo on the French coast would be held the following week. A couple of the yachts had offered to take us aboard for free. We were delighted and were placed on two different yachts.

Sadly, my lifelong struggle with motion sickness soon overcame me and I spent the entire voyage lying on a bunk. I was quickly forgiven by the crew as they won the race despite my mal de mer. Alan had good sea legs and helped aboard his yacht, but they still failed to gain a place in the top three. The crew of my winning yacht were so delighted with their victory that they refused to let us travel on to Paris immediately and instead insisted that we celebrate the victory with them. My green complexion from sea sickness was replaced by a pale shade of grey and a hell of a hangover.

We finally set off confident that we could hitchhike the hundred miles or so to Paris, but we didn’t take into account the bulkiness of the four shapeless canvas bags which contained both our folded up canoes and all our clothing. After hours of futile extending our thumbs at passing vehicles, a tiny car eventually stopped and offered to take as far as the nearest railway station. A large chunk of our hard-earned money from the coffee bar was spent on buying tickets to Paris. Arriving at Gare du Nord station, we struggled a few blocks with the bags to the site of the youth hostel marked on a brochure. Unfortunately, the building containing the hostel had been demolished some weeks previously! The brochure gave us the address of a second youth hostel, miles away in the suburb of Ferme de Malabry. Another large chunk of money went on the bus fare, but we finally arrived, impecunious, exhausted but relieved to have a place to stay for very little expense. The next day we discovered that we were only allowed to stay three nights at any youth hostel. We had spent so much money getting there that we realized we could not hope to travel far on the waterways without earning some money. Even if we worked for three days and left the hostel it would hardly cover a week’s provisions. Our next crisis was the fact that we did not have a permit to work in France. Talk about up the creek without a paddle! (We did have paddles, but they were not about to propel us out of this dilemma.)

Some god or goddess of fortune then smiled on us. After some futile efforts to get a job without a permit, we tried a building site, throwing ourselves at the mercy of the foreman. We explained that in our ignorance we had never thought of getting a work permit. He gave a very Gallic shrug and in surprisingly good English replied “What is a silly piece of paper, eh? You start tomorrow!”

Now we had to sort out our accommodation. Fortune continued to smile. That night two very attractive English girls staying at the hostel invited us for a coffee. Pushing our troubles aside, we accompanied them to a nearby bistro where we explained our problem. The girls shook their heads and said that the warden of the hostel was a monster. He had offered to let them stay at the hostel for as long as they liked but it came at a price – he would sleep with both of them as often as he liked. So far they had resisted but he had issued an ultimatum. Tonight was the night, or else!!!

Alan and I devised a plan. When the warden came looking for the girls, we intervened. He was a young guy, quite tall, good-looking but somewhat overweight. Either Alan or I could have taken him out with ease. With two very fit and angry South Africans confronting him, he quickly caved in. The deal we struck was that both us and the girls would stay as long as we wished. If he came near the girls again, he would end up with his face rearranged.

It didn’t end there. An Algerian was also staying there indefinitely. Goodness knows what pressure he had put on the warden, but he approached us and said for a very small fee he would cook us dinner every night. And boy, could he cook! We feasted night after night on Algerian delicacies, usually supplemented by their staple grain couscous. Sometimes the girls joined us and on other occasions we took them out for a light meal, mindful of the cost of our forthcoming trip.

Our building foreman quickly discovered that Alan and I could unload a lorry packed with cement bags, each weighing about a hundred kilos, quicker than the rest of his crew consisting of twelve Italians and three Frenchmen. He even gave us a small tip. This was not appreciated by the rest of his men, and they did not fraternize with us. We didn’t make matters any easier. Our job was scraping the excess plaster from the wall and ceilings of the rooms they had plastered. In theory we should have filled a wheelbarrow with the excess plaster and wheeled it down ten floors or so on wooden planks laid on top of the stairs.

A South African expression comes to mind – Boer maak a plan! (a farmer makes a plan). We simply threw the plaster out of the window, collected it later from the ground and placed it on the rubbish dump. No objection from the foreman until the day that we went a step too far. There was a corrugated iron hut not far from the building we were working on, which served as the only toilet on the site. One morning one of the other workers, a big fat guy who clearly hated us, went into the toilet. We waited for a short while then started throwing chunks of plaster at the hut. After a few throws we both managed to hit the roof of the hut. Moments later, a terrified and irate Italian rushed out of the toilet with his pants around his knees! Later that day, the foreman with a big grin on his face told us that persons unknown had literally frightened the shit out of Giuseppe. He shook his head and added that he did not expect it to happen again.

Our naughtiness didn’t stop there. We were expected to work on Saturday mornings, but we decided that this was not exactly the way we felt we should enjoy living in Paris, so we never arrived on Saturdays, figuring that sooner or later the foreman would fire us but hopefully by then we would have earned enough to start our trip. After three weeks, a serious-looking foreman called us into his office on a Friday afternoon and told us to sit. Fully expecting to be fired, we looked at each other and gave our version of a Gallic shrug. The foreman reached into a fridge behind his desk and produced a bottle of white wine. He said that it was not likely that we had tried this particular brand, as it was new on the market. He then proceeded to pour us a glass each. We spent a very pleasant afternoon telling the man about South Africa as well as Namibia, Alan’s home. Looking back on it, I think the foreman appreciated that when we did work, we worked very hard and more than made up for our other frivolous behavior.

After a few weeks, the English girls left; the warden hinted that we no longer had any way of blackmailing him. We should definitely consider leaving. Although we would have liked to earn a bit more money, we figured it would take us quite far and with any luck we would find more work along the way. We said goodbye to our foreman who seemed genuinely sorry to see us go, checked out of the youth hostel, and found our way to the banks of the river Seine.

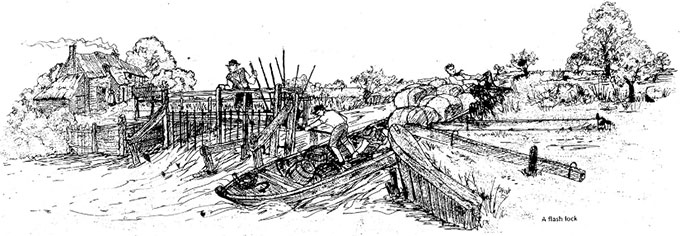

We paddled up stream on a glorious warm afternoon and after about an hour we reached our first lock (écluse in French). A lock is a wonderful invention first created in 984 during the Song dynasty in China. The earliest locks were known as flash locks and were controlled by a single gate.

The later pound locks still in use today have two gates with the boats entering one end and the gate closing after; many boats will fit into the pound (basin). The water level is then raised or lowered according to the level of the river or canal on the far side of the second gate. The second gate is then opened, and the boats leave into the new section of the waterway. Locks therefore allow boats to rise or go down according to the lie of the land. This technical explanation was the least of our worries. The gods had finally deserted us. The lockkeeper saw us approach the lock but before we could paddle into the pound, he stopped us and demanded our permit. Oops! Our fore planning for the trip was virtually nonexistent. We already knew that there were 183 locks between Paris and Lyon, our first major destination.

Did we go on or did we admit defeat and abort the trip? Hell no! We gritted our teeth and realized that we would have to portage our canoes and bags overland to the other side of the lock, at least 183 times. And that only took us part of the way across France! The lockkeeper had no jurisdiction on the river or canal itself, so we lifted our canoes out of the water, humped them about a hundred yards to the other side of the lock and put them back in the water. Sigh!!!

This set the tone for the journey. Every few miles we would haul the canoes around a lock and continue. The worst was when we had already left the river Seine and were paddling along the Canal Latéral à la Loire which took us through the incredibly beautiful Loire valley. We suddenly discovered that the canal had to climb over a hill. Although this feat of engineering was impressive, it didn’t exactly endear the engineers to us. There were ten locks, five going up and five going down, with very little water in between. This meant carrying our canoes and gear about ten miles over the hill without any relief of water! I thought wistfully of arriving at the Paris building site with my daily bottle of red wine, a long loaf of French bread and a box of Camembert cheese. We persevered. By the way, we didn’t have the luxury of a tent. We simply had sleeping bags and slept next to our canoes on the riverbank.

Our money quickly dwindled but we had bought some cans of sardines and some porridge which became our staple diet. We also took the liberty of foraging in orchards alongside the river, grabbing apples, plums, pears, blackberries, etc. I don’t think what we took affected the viability of the farmer’s crop exactly and with wildness of youth we brushed off the guilt of stealing fruit and saw it as simply part of our adventure.

Disaster! We were running out of porridge, which was a vital part of our daily meal. I figured that the chances of finding porridge in France were virtually nil. A day or so later we paddled towards a tiny village on the hillside and decided to see what we could find in the grocer’s shop on the one main street. I pulled out my English/French dictionary and discovered that the French for porridge was flocons d’avoine. Armed with this data I spoke to the storekeeper and asked “Avez-vous flocons d’avoine?” As usual the Gallic shrug. “Je ne sais pas, Monsieur.” I shrugged back, not surprised. We wandered around the shop looking to see what else we could buy and suddenly to my amazement I saw a box of porridge. Gleefully I went back to the shopkeeper and asked how much. His eyes lit up and he exclaimed “Mais oui. Kaker Outs.” I forgave him his pronunciation and delightedly left the shop with a box of Quaker Oats porridge under my arm!

We decided to celebrate so went to a nearby bar and ordered a beer each. The barman asked us in French where we were from. I replied, in my best French, “Afrique du Sud.” His eyes lit up and he smiled “Mais oui, l’Amazon!” I didn’t have the heart to correct him.

Looking back, our adventure was something like discovering the hidden jewels of a new invention, like ExoBrain. Every step revealed something new and sparkling, with the odd setback easily overcome, along the way. The difference being that discovering France was an adventure in delving into antiquity.

Discovering ExoBrain is a venture into a glorious future! I find both a reason to wonder and help expand my horizons.